|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

Vulcan is flying now, and that usually means I go onto other topics, but there are a few things about the program that still confuse me.

I figured one of them out recently, and it is SHOCKING. Or maybe just slightly interesting.

This is going to be an analysis from a business perspective; what sort of competitive environment is Vulcan operating in, with some speculation around why ULA is making the decisions they are making.

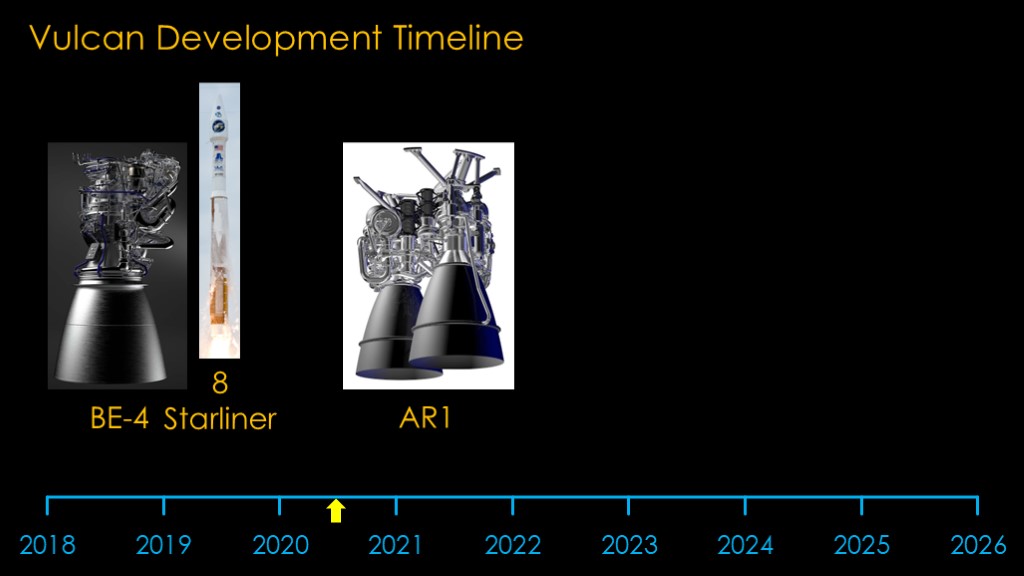

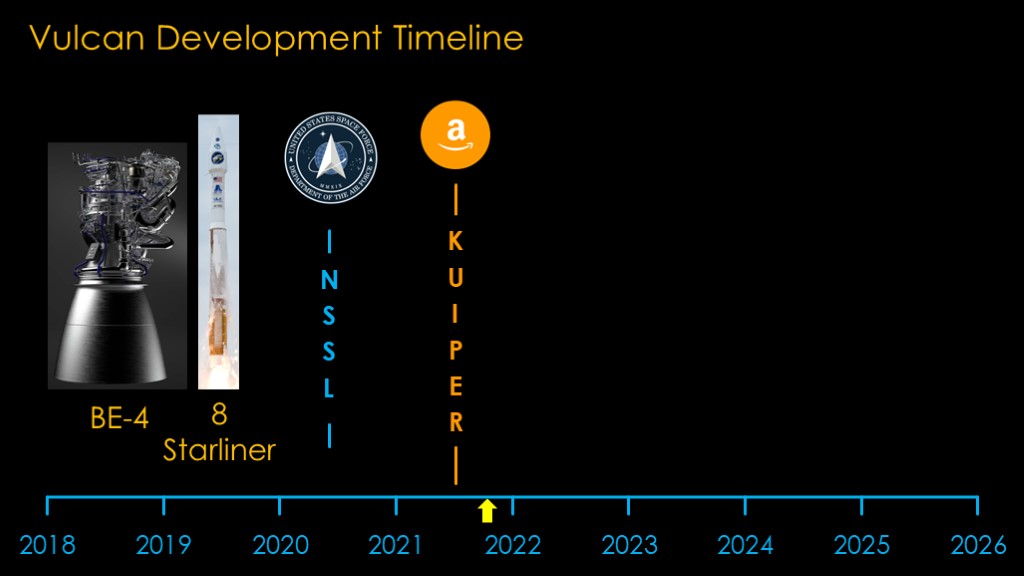

Vulcan development started in about 2014, with a target first launch in 2019.

The first big decision for any new rocket is to choose the engines, as those dictate the design of the rocket.

Because ULA doesn't build their own engines, they were limited to engines they could buy. For the first stage, they looked at the BE-4 that Blue Origin was developing for their New Glenn rocket, and the AR1, an uprated RD-180 clone from Aerojet Rocketdyne. ULA chose the BE-4 in September of 2018.

With that, development was underway, and ULA was targeting mid 2020 for the first flight. That was a very aggressive schedule for a new engine even if it had been under development for 4 years.

In mid 2019, ULA sold 8 Altas V launches to Boeing for Starliner. Boeing was planning on flying soon, and it was a choice between Atlas V and paying SpaceX to launch on Falcon 9, and since Boeing owns half of ULA, they chose to go with Atlas V.

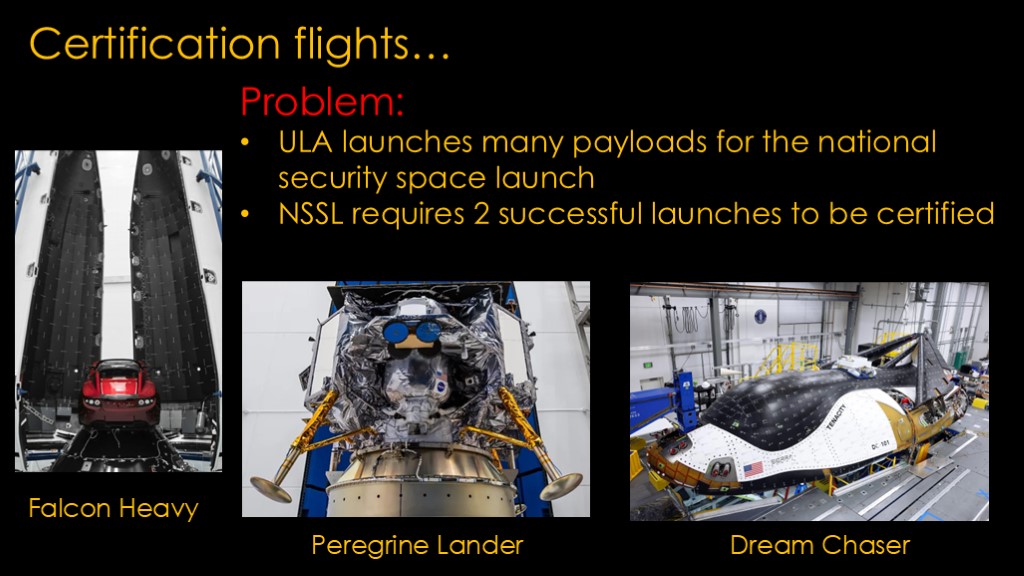

The main customer for Vulcan was national security space launches, but under NSSL rules, they would need to have two successful launches of Vulcan before they could start flying NSSL payloads.

It can be hard for companies to get payloads for their early launches, and if they can't get a payload, they launch a mass simulator. Generally a big hunk of concrete, though for the first flight of Falcon Heavy SpaceX decided to launch a Tesla Roadster.

The obvious downside of a mass simulator is that you don't get paid for those missions.

ULA wanted to get at least a partial payment for those two missions, and they signed up Astrobotics to launch their Peregrine lunar lander and they signed up Sierra Space to launch their Dream Chaser ISS resupply vehicle.

One can argue that this is a bit risky but they are still building and flying Atlas V rockets, and that provides a backup.

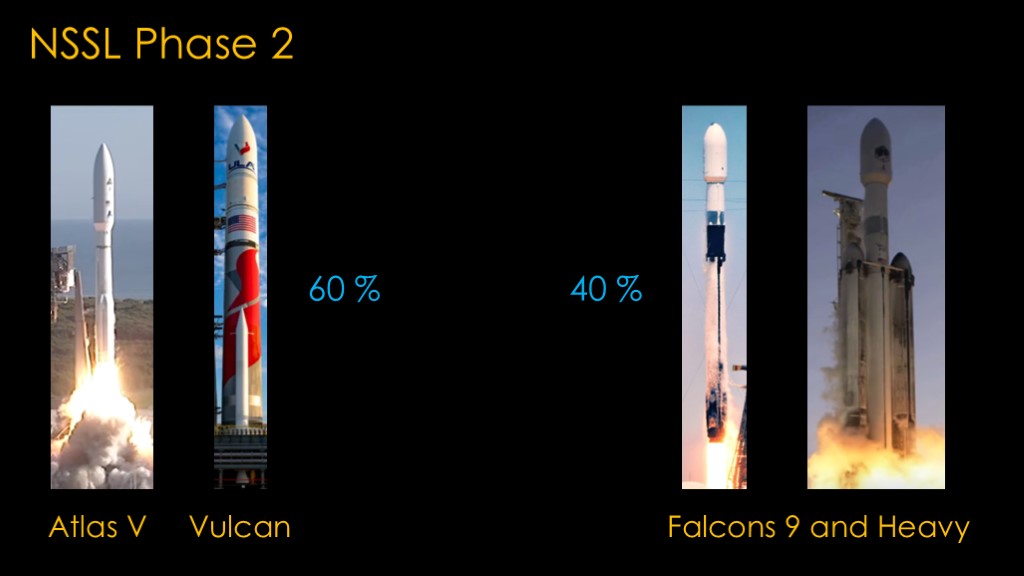

In 2020, the Air Force awarded NSSL phase 2 launch contracts to two companies with a 60/40 split. NSSL covers the majority of the department of defense launches, and this award will cover the launches from 2022 to 2026.

SpaceX wins 40% of the flights with Falcons 9 and Heavy.

ULA wins 60% of the flights using the yet-to-be-flying Vulcan Centaur, currently scheduled to be flying in 2021, but that timeline is a little in flux, so ULA has a backup plan to fly payloads on Atlas V if Vulcan isn't ready. Atlas V can launch the majority of the payloads, though some will require the full power of Vulcan.

This is a very reasonable backup plan, a "keep flying the existing rocket until the new one is ready"...

In late 2020, Vulcan is in good shape.

They have a hard order for 8 starliner flights to fly on Atlas V, the first two payloads lined up for Vulcan, and a NSSL contract that they hope will fly on Vulcan but which can use Atlas V as a backup if Vulcan is late.

The business guy in me says that they are doing a good job at covering their contingencies, to keep flying customer payloads if Vulcan continues to slip. And that's for the customer that has paid them very nicely to launch department of defense payloads for many years, and it seems a sound business decision to keep that customer happy.

They are targeting a first launch in late 2021.

Then Amazon comes calling. They need launchers for their upcoming Kuiper constellation satellites and they buy 9 Atlas V launches, which apparently means that every Atlas V that will exist is spoken for. They can't build more because the Russian RD-180 engine that the Atlas V uses is no longer available due to Russian cutting off the supply.

ULA sold all the Atlas rockets that would be used as backups for NSSL, a program that had in the past put billions of dollars into ULA coffers. And for a constellation launch that while backed by a very solid company, was still a speculative undertaking.

I initially thought that ULA was breaking a cardinal rule of business, which is "never make your biggest customer mad". But I've since realized that this is a very savvy move by ULA. And it comes down to markets...

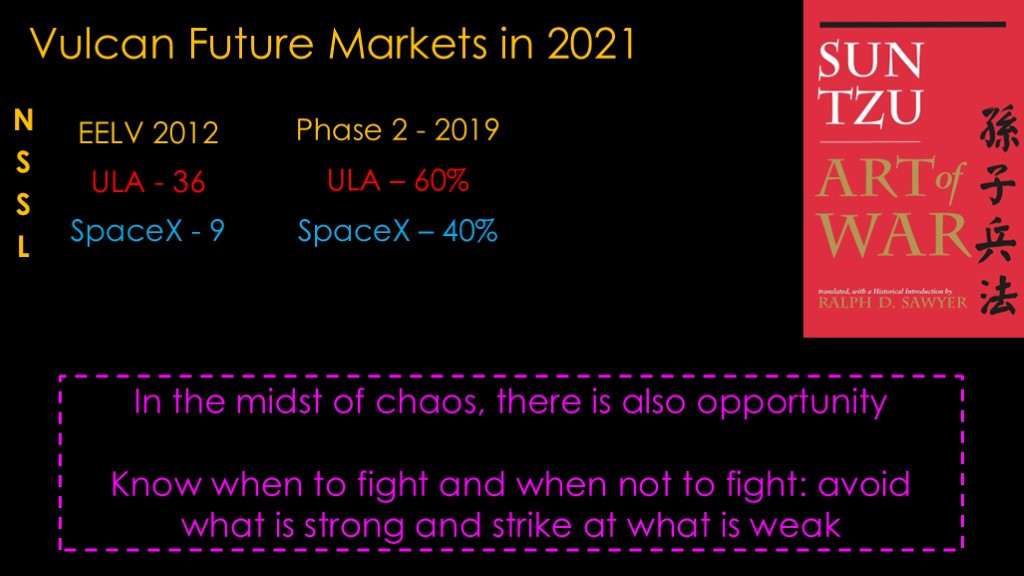

Starting in 2005, ULA was the only US launch provider for the national security space launch program (known as EELV at that time) and they got all the business. In 2012 DoD decided to award ULA up to 36 launches in a block buy and compete another 9. SpaceX initially got 2, sued the air force, and ended up with 9 flights in that chunk.

DoD then clearly decided that they needed a better way of doing this, a way that was actually in compliance with government procurement law, so they spun up a next generation competition. In 2019, ULA wins the 60% share, the yet-to-be-fully-proven SpaceX wins 40%, and Blue Origin and Northrup Grumman go home with a participation medal and a small package of Oreos.

ULA has lost 40% of the business that they had in the past. SpaceX can do all of the missions that ULA can and they are flying a lot of other payloads which means their fixed costs are spread out more. And they've developed this thing called first stage reuse.

Instead of sticking to a strategy that looks unpromising, ULA decides to shift their strategy based on the ancient Chinese military strategist Soon tSoo (Sun Tzu), who lived around 500 BC.

Soon tSoo wrote "in the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity" and "Know when to fight and when not to fight: avoid what is strong and strike at what is weak".

What ULA needs is a market with weaker competition.

That market is the Kuiper Satellite market. The main launchers are:

New Glenn has 12 flights with options for 15 more.

Ariane 6 has a contract for 18 flights, but Ariane 6 is late and there is a large backlog of payloads, with the only firm Kuiper launch set for late 2025. Most of the Kuiper launches are planned for a version with upgraded boosters, which isn't slated to enter service until 2026. Ariane 6 already has 9 other payloads set to launch in 2026.

A wildcard is Rocket Lab's Neutron. Peter Beck is against announcing contracts for rockets that aren't yet flying, so we don't know if they have a contract. Given that Amazon contracted with Ariane, I'd be surprised if they didn't work with Rocket lab.

Atlas V has 9 launches contracted, and Vulcan has 38.

Of the three competitors, I expect rocket lab to be the biggest one. They have a rocket explicitly designed for LEO constellations, the first stage is reusable, the second stage is cheap, and they have experience launching at a reasonable cadence.

The important point here is that SpaceX is excluded - with the exception of 3 launches because of an Amazon shareholder lawsuit - and that gives a much nicer competitive landscape than a company that is launching hundreds of times a year. If there is a salvation for ULA, it is the Kuiper program and it therefore makes sense for them to put Kuiper at the front of the line for everything.

Despite statements that NSSL is their highest priority.

This is also a good deal for Amazon. New glenn first flew in January of 2025 and has not flown again, Ariane 6 has only flown twice and not in the version Amazon needs, and Neutron might fly in late 2025. The only non-SpaceX rocket that they could be sure could start launching satellites early was Atlas V.

Space Force is stuck - they want two providers for NSSL and that means that means dealing with Vulcan being late. They can move some payloads over to fly on Falcon, but they need to send enough payloads to ULA to keep the company alive.

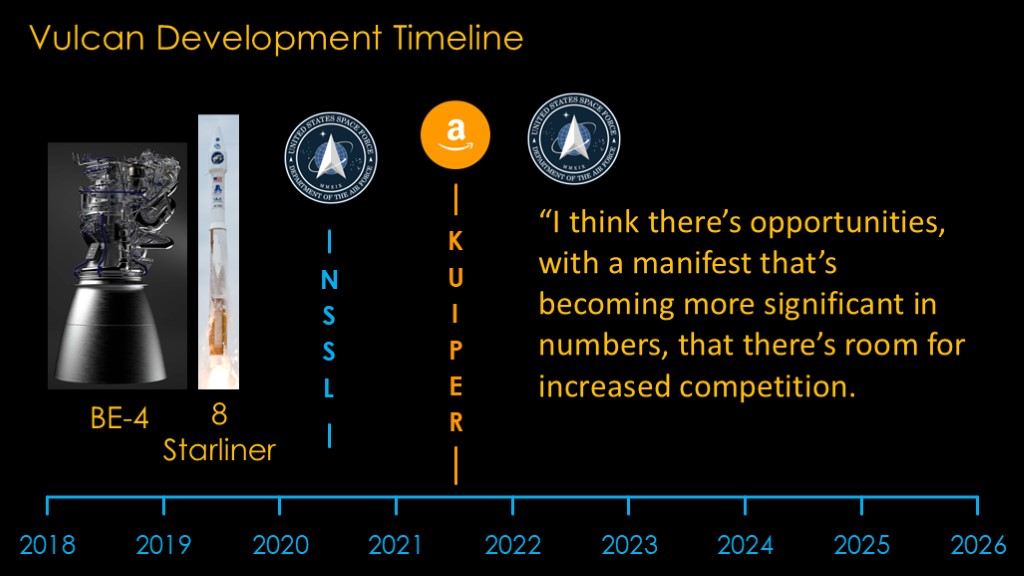

But things aren't static at the Space Force, as they are preparing to open the bidding for phase 3 of NSSL...

In mid 2022, Space force director of Space Operations General John Raymond testifies before congress. He says, "I think there are opportunities, with a manifest that's become more significant in numbers, that there's room for increased competition.

Does that have something to do with ULA putting Amazon ahead of the Space Force? I think it is probably not the only reason, but I strongly suspect it is one of the reasons.

The phase 3 NSSL definition comes out.

It starts with what is called "Lane 1", a competitive bid approach modeled after NASA's launch services program.

As of 2025, the companies in this group are rocket lab, SpaceX, ULA, Blue Origin, and Stoke. Four reusable rocket companies, plus ULA. It's unlikely that ULA can make money in this lane.

Lane 2 started out as the traditional approach with a 60/40 percent split between two providers, but in a revision, the Space Force says that they are will add a third provider in a smaller role. Some people - included me - have asserted that this is the result of lobbying by Blue Origin, and while I still think there is some truth in that, I also view this as a reaction to ULA's choice to prioritize Kuiper over NSSL launches.

When the competition is over, lane 2 ends up with SpaceX getting 52% of the launches, ULA getting 35%, and Blue Origin getting 13%, assuming the New Glenn can meet the launch requirements by the end of 2026.

Before 2012, ULA got 100% of the launches, in the 2012 section they got 80%, they got 60% in phase 2, and 35% in phase 3. Phase 3 is actually worse than 35% as ULA isn't getting Lane 1 launches. It's not as bad as that; NSSL is launching a lot more in phase 2 and phase 3 so the number of launches for ULA doesn't go down as much as you would expect.

Going forward, I expect that in phase 4 lane 1 will get bigger and lane 2 will get smaller. It's also possible that Blue Origin could take the second award and ULA could be stuck with third place.

We now skip forward a few years. Vulcan has been waiting for BE-4 engines from Blue Origin. It is no surprise that the BE-4 is taking some time; the BE-4 and Raptor are the only two staged combustion engines developed in the US since the space shuttle main engine in the 1970s.

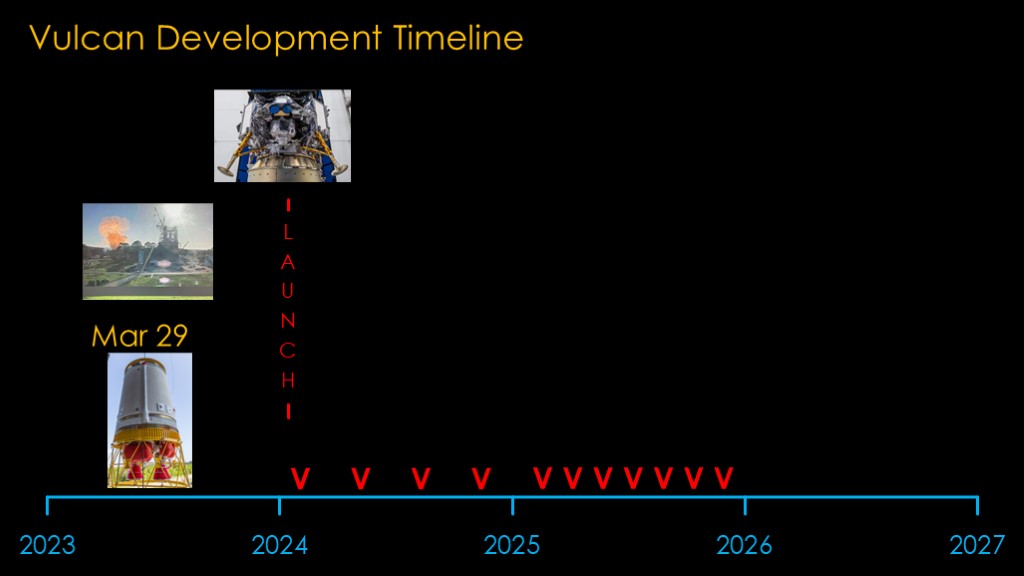

In 2023 ULA is moving towards the first Vulcan launch, but on March 29 the Centaur V upper stage they are testing has a failure of the hydrogen tank and that leads to an explosion.

This has me very confused. ULA had a pathfinder - an initial test version of the first stage - under test in February of 2021, but for some reason they delayed testing the brand new Centaur V second stage until right before they were planning to launch.

This makes absolutely zero sense to me; they lost perhaps 6 months of schedule time with a failure that they could have found years earlier.

Despite the continued Vulcan delays - and the complaints from the Space Force about them - ULA does not move any NSSL flights to Atlas V, reinforcing the idea that NSSL is now their SBFF (second best friend forever).

Coming up towards 2024, here is the overall status.

Peregrine - the first flight payload - is ready to launch, and there's a Vulcan at the pad to launch it.

ULA is planning 4 Vulcan launches for 2024, and 7 for 2025. Assuming that the Peregrine and dream chaser launches both go well, that gives them a chance to get two NSSL launches in. Four launches is a good target for 2024, and 7 for 2025 is also a good target.

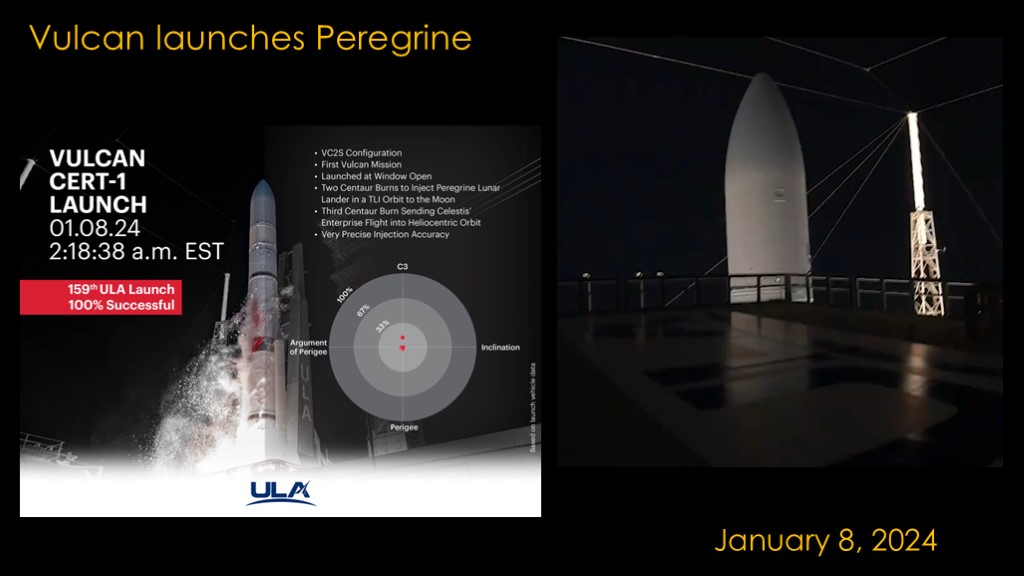

Finally, on January 8th, 2024, Vulcan takes off with Peregrine aboard.

The launch is about as perfect as it could be, and ULA declares it to be 100% successful. Peregrine has issues, but not because of Vulcan.

This is a major step for Vulcan, but leads to a significant quandary for ULA...

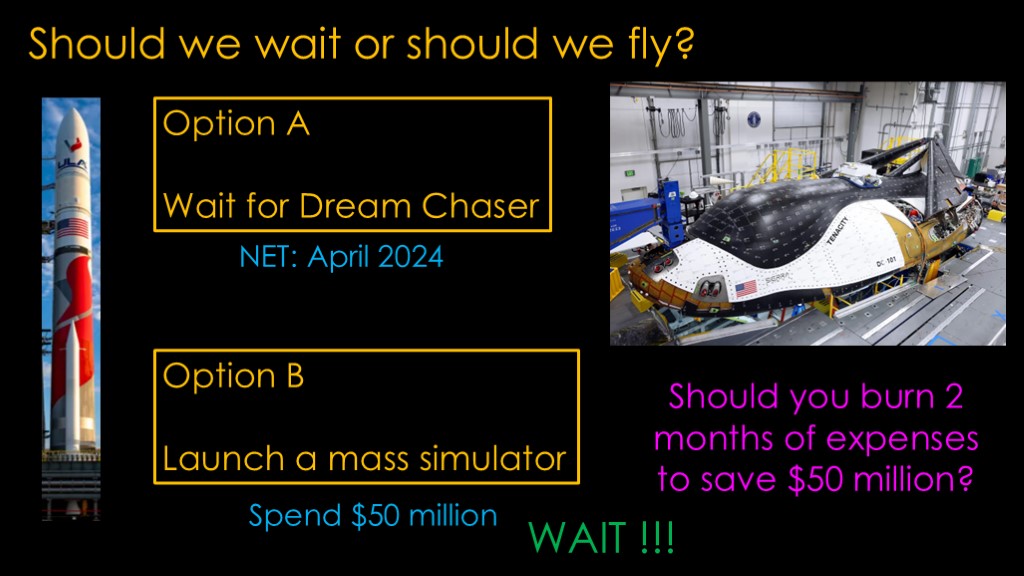

Should they wait or should they fly?

Their first option is to wait to fly dream chaser. This is the preferred choice - it gets a flight off their backlog and should get Vulcan certified.

The second option is to launch a mass simulator instead of waiting.

Dream chaser will be ready in April 2024 - 2 months from now - and the mass simulator option will waste a rocket and cost us at least $50 million.

Should you burn 2 months of expenses to save $50 million? A company like ULA has ongoing fixed costs - costs to keep their facilities running and their people employed - and when you are waiting, you are by definition burning money.

That seems like a pretty simple question to answer, given the way I've framed the question. It's pretty clearly "Wait!"

But notice that NET in the date, which means "no earlier than"...

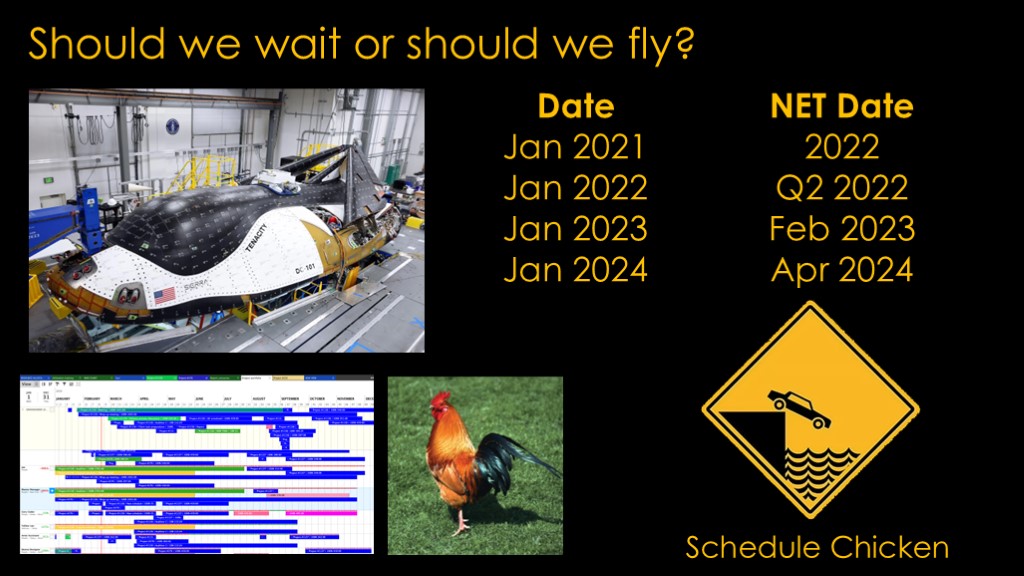

Before we make this decision, maybe we should look at the dream chaser history.

We see that in January of 2021 it was scheduled for 2022, then for 2022, 2023, and 2024, it's scheduled for later that year.

That looks like the pattern you would see when a payload is waiting for a launcher to be ready. They have to slip their date whenever the rocket slips.

But it could also be schedule chicken. A project with multiple teams often runs late and is in danger of driving off the schedule cliff. It is a bad thing to speak up and say you need more time, as you become the *cause* of the schedule slip. Then the other teams - who are generally as behind as you or more behind - can say "we could hit the earlier date but we can make productive use of the extra time". Which makes them look good.

So, teams play schedule chicken, trying not to be the team that blinks and becomes the cause of the slip, the slip that everybody is counting on. Many large software groups have turned schedule chicken into an art form.

This is not to cast aspersions on the folks at Sierra Space - Dream Chaser is a very complex and innovative vehicle and those sort of projects are inherently very hard to estimate. We should view their schedule with a big helping of skepticism.

We also know that ULA has been building new Vulcan hardware, as shown in the pictures that CEO Tory Bruno has been sharing.

So, what should ULA do?

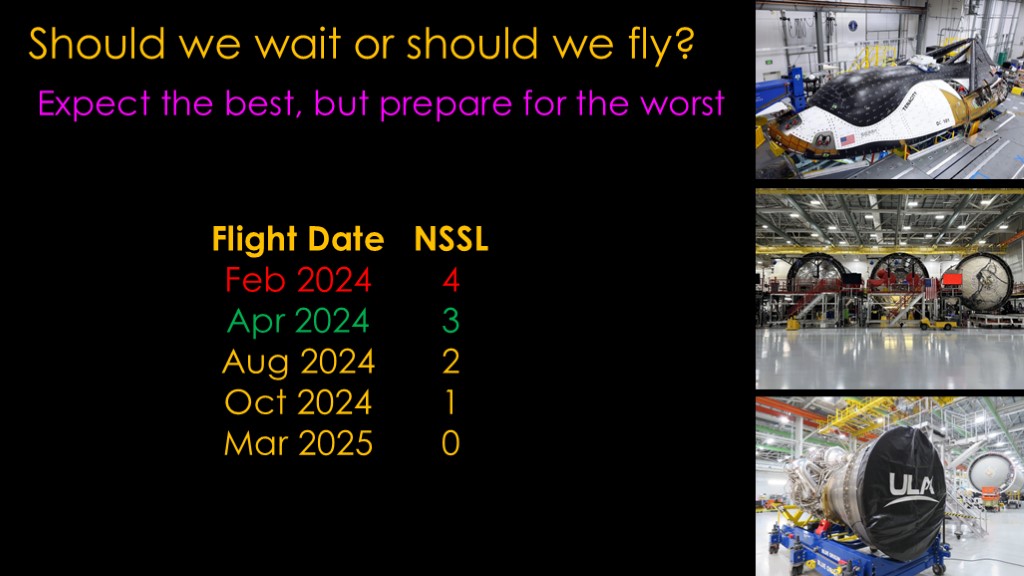

Sun tZoo tells us to expect the best but prepare for the worst.

Let's build a little table to explore the options.

ULA can launch a mass simulator right away, in February of 2024, and with good luck, could get certified and launch up 4 NSSL payloads in 2024.

If Dream Chaser flies in April, that's a 2 month delay but there is likely time to get certified and launch 3 payloads.

If it's delayed until August, that's 2 payloads, in October, 1 payload, and if it's delayed until March of 2025, that's obviously zero payloads.

The ideal outcome is Dream Chaser launching in April - it saves money and gives almost the same number of payloads. The worst outcome is Mar 2025 for Dream Chaser, and launching zero payloads.

Let's say the worst that you can tolerate is two NSSL launches, and that will require the certification launch by August.

ULA decides to wait for the April date. They have better data than any of us on the outside do, but I think it would be prudent to have a mass simulator at the launch site so that if Dream Chaser slips, you have ample time to launch either in April or perhaps August at the latest.

We get to April, and Sierra Space says that Dream Chaser is now aiming for the last quarter of 2024. If you think you are going to be done in 3 months and after 3 months, you have a 6 month delay, that is not a sign that you will be ready in 6 months. This is a sign that your estimates are not trustworthy. Feels like schedule chicken to me.

At this point, ULA has the best chance of getting multiple NSSL launches if they fly a mass simulator immediately, using a Vulcan already at the launch pad and ready to go and a mass simulator sitting there as a contingency payload. That costs them money but they don't waste any time and with luck they can still get a few flights for NSSL in 2024. They avoid the worst case scenario.

They do talk about this in May but say they are still confident in the October date, which utterly confuses me. It feels like they haven't been gaming out the options and they are unprepared for the slip; it took them a *month* to come up with a contingency plan, a plan that they honestly should have had in place before the flight of Peregrine in January.

Then they spend another 6 weeks waiting before they decide in late June that Dream Chaser isn't going to make an October date. It will take 3 months for them to get ready to launch a rocket that was supposedly ready to fly a payload in April.

ULA has bought something close to the worst-case scenario. They lose 6 months waiting to fly *and* they have to pay the money for a mass simulator launch. They still hope to launch in October, get certified, and fly two payloads by the end of the year.

This is the sort of decision that has me really confused. Time is the one thing that you can never get back, and ULA's decision to wait means that they are less likely to get any NSSL revenue in 2024.

Worse, one of the justifications for their high price is high schedule reliability. Not on Vulcan, apparently

In the mass simulator flight that they hope will lead to quick certification, ULA catches a bad break. One of the nozzles on the GEM 63XL solid rocket motor breaks apart. But they catch a good break in that the way the nozzle broke sent most of the exhaust away from the rocket; if it had broken on the inside, it easily could melt the BE-4 engines and that would be very bad.

Under NSSL rules, ULA is allowed to take a fast track approach to Vulcan certification because the rocket is derived from the Atlas V. These SRBs are a new version and ULA has to go through a full anomaly investigation and will probably get extra homework from NSSL to complete before they are certified.

ULA launches zero NSSL payloads on Vulcan in 2024 and their rocket is not certified for NSSL. They already decided they wouldn't launch on Atlas V. ULA threw the dice and hoped to get lucky and ended up with the worst case scenario.

Then we get to the next weird thing. Or at least a thing that seemed weird at first.

After the cert 2 flight, they immediately start stacking the next Vulcan rocket in anticipation of the first NSSL launch. This is a really smart thing - get the rocket in their integration facility and tested as soon as possible. They are 4 NSSL launches behind where they wanted to be and need to do anything they can to be ready when they get certified.

The certification process drags into the next year.

Early in the new year, Amazon stops by and says, "Hey, we have some Kuiper satellites ready to launch", and ULA replies "Sir, Yes Sir!"

They therefore start destacking the Vulcan that is ready to launch in early February so they can stack an Atlas V to launch Kuiper satellites.

This destacking is required because ULA only has one integration facility at their launch pad. There is another one under construction, but it won't be ready until later in 2025 at the earliest. This is another thing they could have addressed during the delays.

The certification is completed in late March, which meant Vulcan probably could have launched by the end of April.

At the end of 2024, ULA was forecasting up to 20 Vulcan mission in 2025.

By April, that was revised down to 11-13 total mission in 2025, with a roughly equal split between Vulcan and Atlas V. That means that the Vulcan count went from 20 to 6 in 3 months.

The first Atlas V Kuiper launch flew on April 28th, 2025, and my guess is that they will fly another Kuiper mission before the first NSSL launch on Vulcan, currently scheduled for "summer".

The record for launches from ULA's space launch complex 41 at cape Canaveral is 8 in a year. They're launching two different rockets, one of which has only flow twice, and they've flown once in the first 4 months of 2025.

11 to 13 launches seems somewhere on the continuum between challenging and unrealistic. I asked my twitter followers how many launches ULA would make in 2025, and the average was 5.2. That seems like a pretty good guess to me.

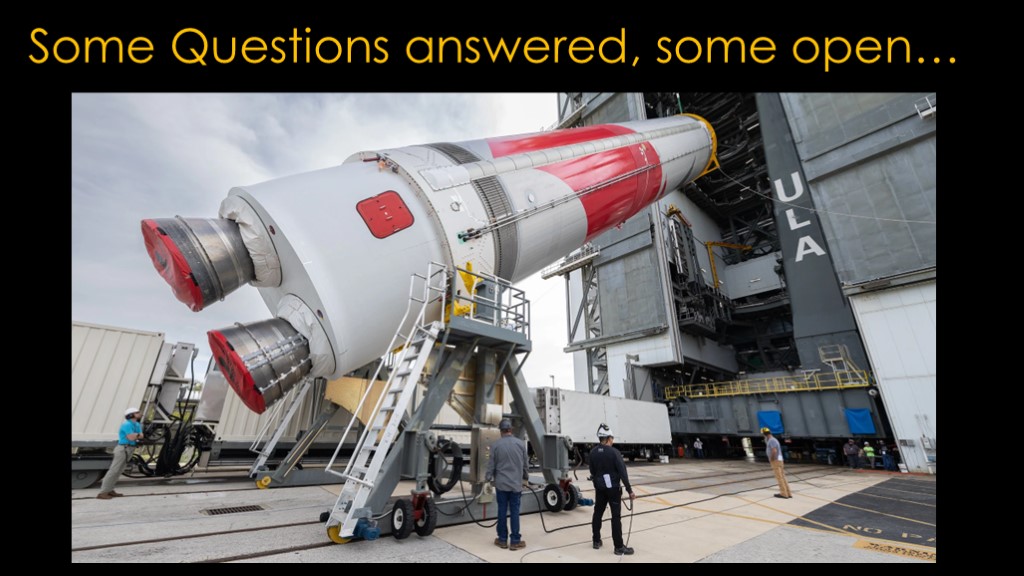

I have three unresolved questions.

Why did they wait to perform the Centaur V test for years?

Why did they trust Dream Chaser schedules, especially after they slipped 6 months in 3 months of time?

Why didn't they have a Vulcan already stacked and ready to launch a mass simulator when they finally decided Dream Chaser wouldn't be on time.

These are all "own goals" and have cost them at least a year of time, and perhaps $500 million in revenue.

I have a few thoughts on why...

The first possibility is management...

Tory Bruno is probably my favorite Old Space CEO and taking ULA from a company that launched Atlas V and Delta IV from fully disconnected infrastructures to one that has a single rocket is a big accomplishment. They aren't quite there, but they are getting close.

It's easy to forget that while Tory is President and CEO of united launch alliance, ULA is wholly owned by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, two companies that are looking after their own company success when they make decisions related to ULA. And they pretty much hate each other.

At best, it has to be a very trying relationship and a slow way to make decisions...

The second possibility is that Vulcan is - or at least was - late.

My assumption is that in 2024, ULA had Vulcans a plenty, but let's assume that they were only expecting two flight vehicles in until late in 2024.

If you don't expect more Vulcans to be flight-ready until the fall, then flying the mass simulator in April of 2024 doesn't help - you can't fly operational missions until the fourth quarter *anyway*. At that point delaying to see if Dream Chaser makes it is the right business decision, and you can use the dream chaser delay as a bit of a smokescreen. Assuming you are confident that you won't have an issue on the cert flight.

Is there any evidence for this?

The tank failure of the centaur V could have been a factor, but given that they finished the investigation and a fix in time for the Peregrine flight, it seems unlikely. And Tory Bruno described the change as an easy fix - they put a band around the top of the tank.

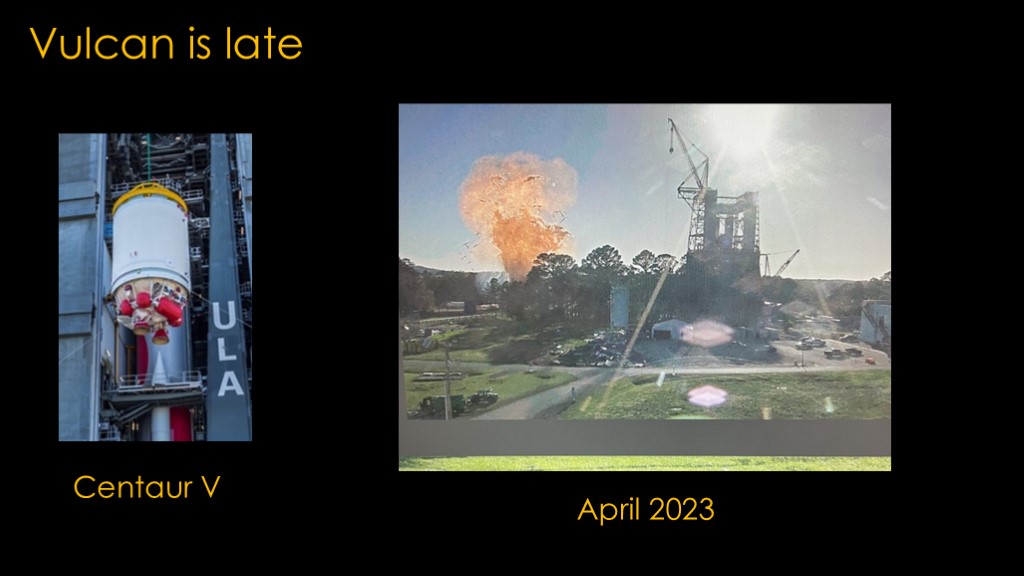

The other possibility is that there were availability problems with the BE-4 engines. Is there support for that idea?

Here is the second BE-4 being installed in the second booster in mid April, 2024. The engines for the first flight booster were installed in October of 2023, and 6 months seems like a long time to wait for the second one to be ready. If this is happening in their factory in Decatur, Alabama halfway through April it's pretty clear they weren't hitting an April launch date even if Dream Chaser was ready, nor were they ready to launch a mass simulator

Bruno has consistently said that BE-4 engine availability is not an issue, but this makes it look like there was an issue in the spring of 2024 at the very least.

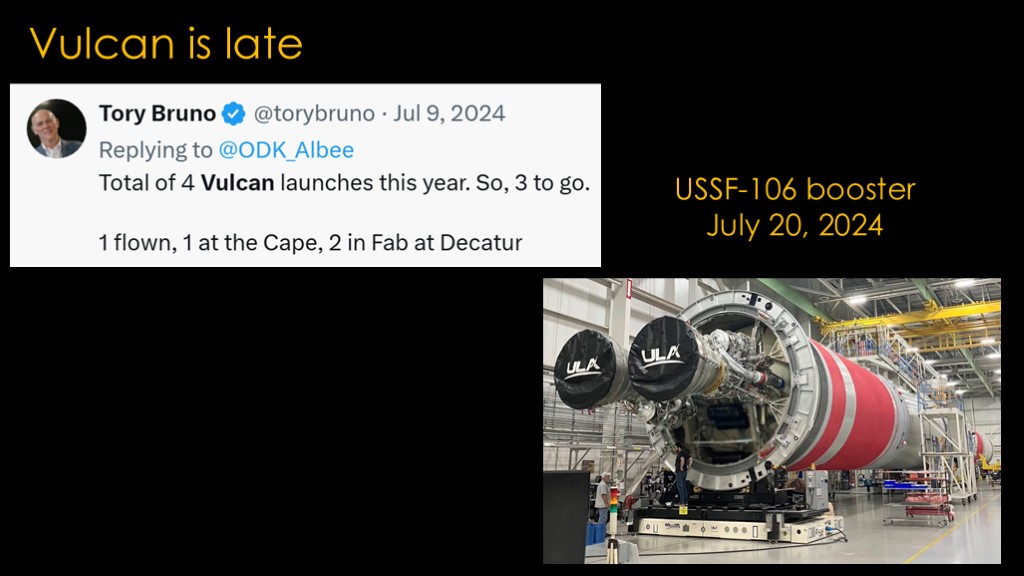

In mid July of 2024, Tory Bruno tweets that they have flown one Vulcan (the cert 1 mission with Peregrine), have the second Vulcan sitting at the cape, and 2 more in fabrication at their factory in Decatur, Alabama.

Here is the third booster - the one that will fly USSF-106 for the space force on the first operational mission - almost ready to ship to Cape Canaveral in late July.

The existence of this booster suggests that they could have flown this mission in September if they had flown the mass simulator mission in July - and hadn't had the anomaly. It seems they still burned perhaps 3 months of time.

And that's the Vulcan update. The pivot to favor Amazon over the Space Force makes sense, but it's very unlikely to make them friends in the Space Force.

My estimate is that they lost 18-24 months due to their decisions, but it seems likely that they wouldn't have had engines to launch earlier than 2024.